The World of Art

Why Are Ultra-Contemporary Artists Returning to the Old Masters?

In an era defined by artificial intelligence, algorithmic feeds, and image overload, a growing number of young and mid-career artists are grounding their practices in art history. From the Renaissance to the Baroque and beyond, references to canonical European painting are resurfacing across galleries, foundations, and museums particularly in New York. But this revival is more than aesthetic nostalgia or market-driven name-dropping. It reflects a deeper search for meaning, material authenticity, and historical continuity in a destabilized digital age.

A Tradition of Reinterpretation

Artists have always looked backward to move forward. The Auguste Rodin studied Michelangelo; Pablo Picasso revisited Rembrandt; even ancient Roman artists reinterpreted Greek precedents.

TodayŌĆÖs ultra-contemporary generation continues this lineage but with new urgency. As technology accelerates and A.I. systems replicate stylistic languages in seconds, artists are turning to historical methods and philosophical frameworks as anchors of authenticity.

This renewed dialogue with the past is especially visible in New YorkŌĆÖs current exhibition landscape, where emerging and established artists are openly engaging with figures ranging from Donatello to Francisco Goya.

Material as Meaning: Rediscovering Technique

One key driver behind this return to Old Masters is material consciousness. Rather than merely referencing iconic imagery, artists are immersing themselves in historical techniques, pigments, and processes.

For example, painters influenced by the Northern Renaissance revisit the visual austerity of Hans Memling and Hans Holbein the Younger. Their work often explores rural identity, portraiture, and the tension between pastoral myth and contemporary life filtered through centuries-old glazing methods and layered oil applications.

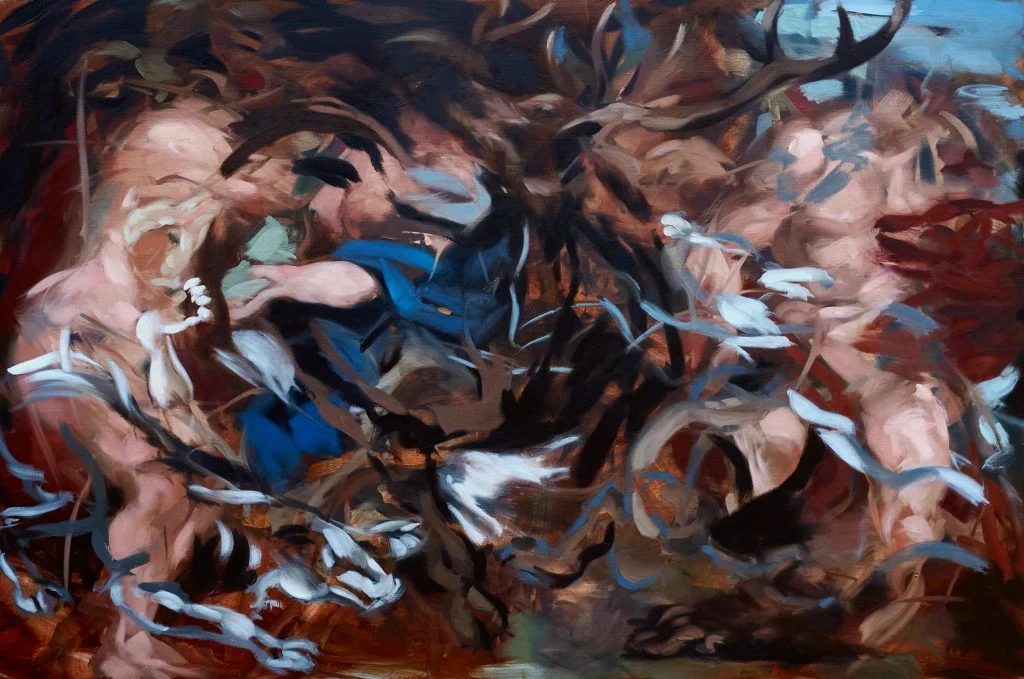

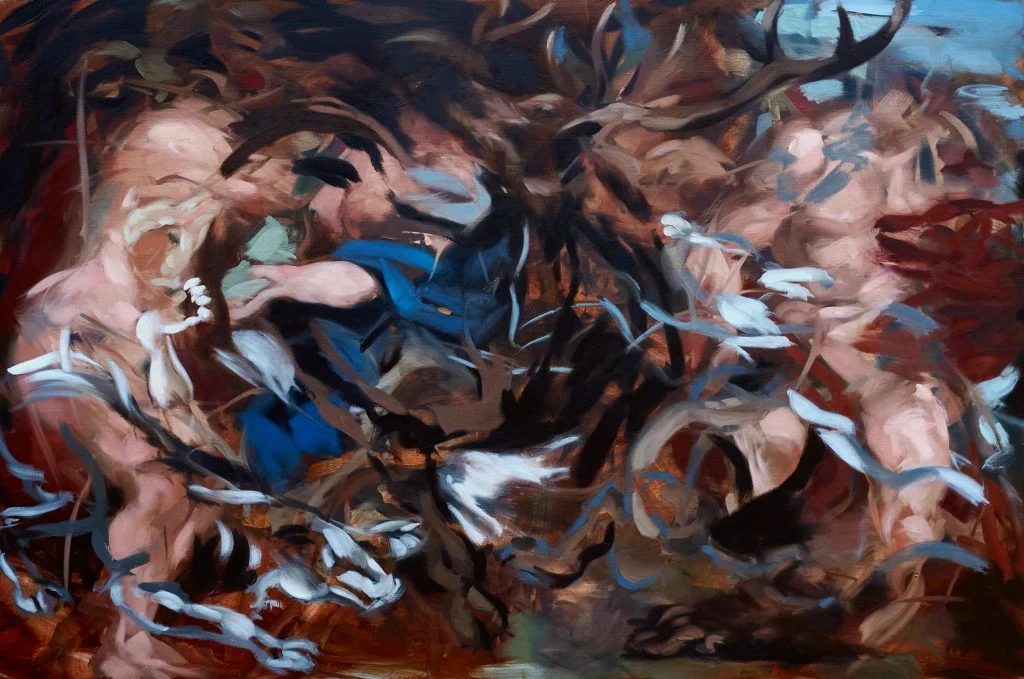

Similarly, contemporary artists inspired by Flemish Baroque traditions draw from Peter Paul RubensŌĆÖ dynamic compositions. Techniques such as alla prima (wet-on-wet painting), pentimenti (visible revisions), and multi-layered glazing reappear in works that echo RubensŌĆÖs intensity without directly imitating it.

In these practices, the medium is not secondary it is central. Historical technique becomes both conceptual framework and aesthetic strategy.

Art History in the Age of A.I. and the Endless Scroll

The resurgence of Old Master references is also a response to technological anxiety. Media theorist Marshall McLuhan warned in the 20th century that electronic media would produce sensory overload and cultural numbness. In 2026, his predictions feel strikingly relevant.

Artists today operate within a relentless digital ecosystem an ŌĆ£endless scrollŌĆØ of disposable images. By grounding their work in art historical precedents, they resist ephemerality and reclaim depth.

This phenomenon raises larger questions:

-

What does originality mean in the age of generative A.I.?

-

How do we create significance in a culture saturated with visual references?

-

Can historical continuity counteract digital fragmentation?

Some painters openly ŌĆ£borrowŌĆØ poses, compositions, or atmospheres from figures like ├ēdouard Manet, Jean-Antoine Watteau, Giorgione, or Giorgio Morandi not to replicate them, but to destabilize their authority. By dispersing references across centuries, they transform canonical compositions into open-ended emotional frameworks rather than fixed historical monuments.

Market Shifts and Cross-Generational Collecting

This transhistorical conversation is not limited to studio practice it extends to collecting behavior. Art fairs such as Frieze Masters have reported renewed interest in historical works alongside cooling enthusiasm for ultra-speculative contemporary markets.

Younger collectors increasingly mix categories: pairing a contemporary figurative painting with an 18th-century canvas, or integrating Old Master works into collections that also include design objects, fossils, and postmodern collectibles.

This ŌĆ£cross-pollinationŌĆØ broadens audiences. Historical references make contemporary works more accessible to collectors familiar with classical art, while contemporary reinterpretations refresh interest in overlooked historical artists.

Beyond Formalism: A Metaphysical Dialogue

Museums and foundations are also embracing cross-temporal curating. Institutions such as The Frick Collection and The Metropolitan Museum of Art increasingly stage dialogues between Old Masters and living artists.

These exhibitions are not merely stylistic pairings. They provoke deeper questions:

-

What connects human experience across centuries?

-

How do themes of mortality, power, beauty, and identity persist through time?

-

Can historical imagery offer stability amid technological acceleration?

When contemporary artists reinterpret Renaissance or Baroque strategies, they are not retreating into nostalgia. Instead, they are confronting the instability of the present through the durability of the past.

Why This Trend Matters Now

The renewed fascination with Old Masters among ultra-contemporary artists reflects three intersecting forces:

-

Technological Unease ŌĆō A.I. and digital replication challenge notions of originality.

-

Material Revival ŌĆō Artists rediscover the intellectual and physical depth of traditional processes.

-

Cultural Anchoring ŌĆō In uncertain times, art history provides continuity and perspective.

Ultimately, this movement is less about imitation and more about recalibration. By revisiting art historical foundations, todayŌĆÖs artists test how meaning survives in an era where time feels compressed and images multiply endlessly.

The dialogue between past and present is not a regression it is a strategy for navigating the future of art.